|

The Australian

The Times

August 01, 2015

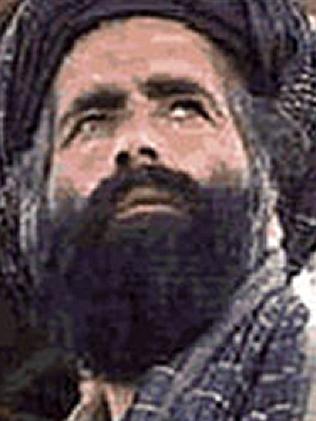

Mullah Mohammed Omar. Born in 1960. As now acknowledged, died in April 2013 in Karachi Pakistan

Of all the men on America’s most wanted list during the “war on terror”, the spiritual and political leader of the Taliban, Mullah Mohammed Omar, proved to be among the most mysterious and elusive.

The ethnic Pashtun was the force behind the Taliban’s seizure of power in Afghanistan in 1996, leading a grassroots army that conquered almost all of the country and imposed order on its citizens after two decades of war and anarchy, and which provided a base for Osama bin Laden and al-Qa’ida. Having quelled the criminal fiefdoms tearing his homeland apart, Omar assumed the mantle of a modern-day prophet as he donned a cloak said to have been owned by Mohammed himself. He became the first Muslim in 1000 years to take the title “Commander of the Faithful”.

From 1996 to 2001, Omar was in effect the head of state — a shy fanatic who rarely left his headquarters in the southern city of Kandahar. With so little insight into the man, reports on him varied.

To some he was a benighted peasant whose ignorance of world affairs had been exploited by unscrupulous operatives in al-Qa’ida. To others, he was a shrewd leader in the warrior-like traditions of Afghanistan and a fervent ideologue.

Either way, his stubborn refusal to accede to US demands to hand over his “guest” bin Laden after the attacks of September 11, 2001, brought heavy retribution — the US-led coalition invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 and ousted the Taliban.

In the early days the Americans thought that the Taliban might bring permanent peace to the country, making it possible to construct pipelines carrying gas and oil from Central Asia through Afghanistan. Omar quickly dispelled such hopes by speaking about the need to destroy the US. Reports of the regime’s brutality also began to surface.

Omar’s aim was to restore religious purity through Sharia, with the result that Afghan life was plunged into an antediluvian past. The popular pastime of kite flying was banned. Television, radio, cinema, football, music, and other sources of “Western decadence and pornography” were proscribed. The offices of foreign NGOs were closed and all aid was entrusted to Allah. Anything “culturally alien” was destroyed. In March 2001 two huge statues of the Buddha — the world’s largest — at Bamyan, dating back to the 3rd and 5th centuries, were blown up.

Women were prevented from receiving an education or working. In a country with thousands of war widows, this created hardship. When women were allowed to leave the home to shop for food, they were forced to wear the burka, which concealed them. Those who showed so much as an ankle were likely to be severely beaten by the religious police.

Men were compelled to grow long beards — police hairdressers were on hand to rectify any deviation. Adultery and homosexuality were punishable by death, theft by amputation of a hand. Public executions were carried out at the sports stadium in Kabul.

Even after the US had toppled the Taliban, Afghanistan’s unforgiving desert and mountainous terrain was still suffused by the influence of Omar, who was believed to be co-ordinating an insurgency from a refuge in the Pakistani city of Quetta.

Omar was born into a family of landless peasants in a village near Kandahar in 1960. His father was an itinerant preacher who died when Mohammed was five.

The young Omar studied at a madrassa, becoming a mullah in the village mosque of Singesar in Kandahar province. He later learnt Arabic and became devoted to the hardline teachings of the Palestinian Sunni cleric and founder member of al-Qa’ida, Abdullah Azzam.

During the war against the Soviet invaders after 1979, Omar took up arms. Tall and warrior-like with dark features, he was a natural soldier and became a commander in Singesar, gaining a reputation for his attacks on enemy tanks.

He lost his right eye after being hit by shrapnel from a Soviet rocket. According to popular legend, he removed the eye and stitched up the empty socket himself. In fact, it was surgically removed at a Red Crescent hospital. On the evening of his injury, Soviet forces withdrew, and Omar is said to have risen from his hospital bed with his face wreathed in bandages and sung a ghazal, or traditional poem, as he celebrated with comrades.

After the Russians withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, there was an uneasy alliance between the Tajiks of Ahmad Shah Masood and the Uzbeks of Abdul Rashid Dostum, but by 1992 they had overthrown the Moscow-backed regime that took over when the Soviets left. Kandahar was effectively ruled by criminal fiefs who routinely terrorised the population.

In 1994, a committee of war veterans is said to have gone to Omar’s home and asked him to restore order. “He said nothing for some time. This was one of his common habits,” recalled one of his cohort, Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef, in a memoir. Finally, he agreed with their plan. Soon afterwards, Omar was told that in a nearby village a local commander had abducted two teenage girls and repeatedly raped them. He gathered 30 of his followers and assailed the errant commander in his base, stringing him up from the barrel of his own tank. News of this spread. Omar’s authority grew.

The movement was named Taliban, meaning “students of Islam”. Within two years the Taliban had swept through southern Afghanistan. They initially met fierce resistance from president Burhanuddin Rabbani’s forces, but by late 1995 they were in the ascendant. Thereafter there was relatively little bloodshed because the Taliban had ample funds to buy off opponents; it is almost certain that Inter-Services Intelligence, the Pakistani military intelligence service, supplied the Taliban with money, as did Saudi Arabia. The Taliban also made huge sums from opium production.

Omar entered Kabul in September 1996 and ordered the execution of the former president Mohammed Najibullah. He was dragged from the UN compound where he had taken refuge, and, according to several sources, castrated before being dragged to his death behind a truck and strung up in public. A month later Omar pronounced the establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, with himself as emir. He continued to base himself in Kandahar, where he had four wives and dispensed wads of dollars to his commanders. His large house and a Chevrolet truck were said to have been paid for by his friend bin Laden.

Some reports said that they had known each other while fighting against the Russians, others that the friendship only began after bin Laden’s arrival in Kandahar from Sudan in May 1996 when he put himself under Omar’s protection. The two men spoke almost daily by satellite telephone. Bin Laden may have married one of Omar’s daughters, and vice-versa. It is claimed that bin Laden sought to open the eyes of this essentially provincial cleric to global Islamic fundamentalism.

When George W. Bush demanded that Omar hand over the al-Qa’ida leader, he is reported to have said that there was a “less than 10 per cent chance” of the US carrying out its threat to invade a territory that over centuries had proved to be indomitable. He was wrong. Land operations began in October 2001 and Omar went into hiding. His house in Kandahar was bombed and his stepfather and 10-year-old son were killed. Washington offered $US10 million, later raised to $25m, for information leading to his capture.

Omar still commanded the allegiance of pro-Taliban leaders in the region. US intelligence believed that he remained a key figure in the insurgency. Various reports in later years suggested that he lived in Quetta and then Karachi under the protection of the ISI. He is reported to have suffered a heart attack, but his death was only confirmed by the Taliban after Afghanistan’s National Directorate for Security reported this week that he had died in hospital in April 2013.

The Taliban published a biography of Omar — who never gave an interview to a Western journalist or allowed himself to be knowingly photographed — in April this year. In the book he was portrayed as a “tranquil” figure who rarely lost his temper, was a “good listener” and had a “special sense of humour”. The RPG7 was listed as his “favourite weapon”.

During the Obama administration, efforts were made to bring the Taliban into peace negotiations; some reports said that Omar was willing to talk but that he was not as influential as he had been. US intelligence believed that he was still the key man.

Omar is believed to have taken his loyalty to bin Laden and his devotion to holy war to the grave. When Prince Turki bin Faisal al-Saud of Saudi Arabia secretly visited Omar to urge him to hand over bin Laden to the Saudis in the autumn of 2001, the Taliban leader is reported to have disappeared and re-entered the room soaking wet.

He had poured cold water over his head to cool down, he told the prince, and would have killed him had he not been a guest. THE TIMES