Morrison, Hayden and Cosgrove and their faith

Article by Greg Sheridan

Weekend Australian

31st July 2021

Scott Morrison, Bill Hayden and Peter Cosgrove discuss their paths to religion and the role it plays in their lives

Go to Bill Hayden

Go to Peter Cosgrove

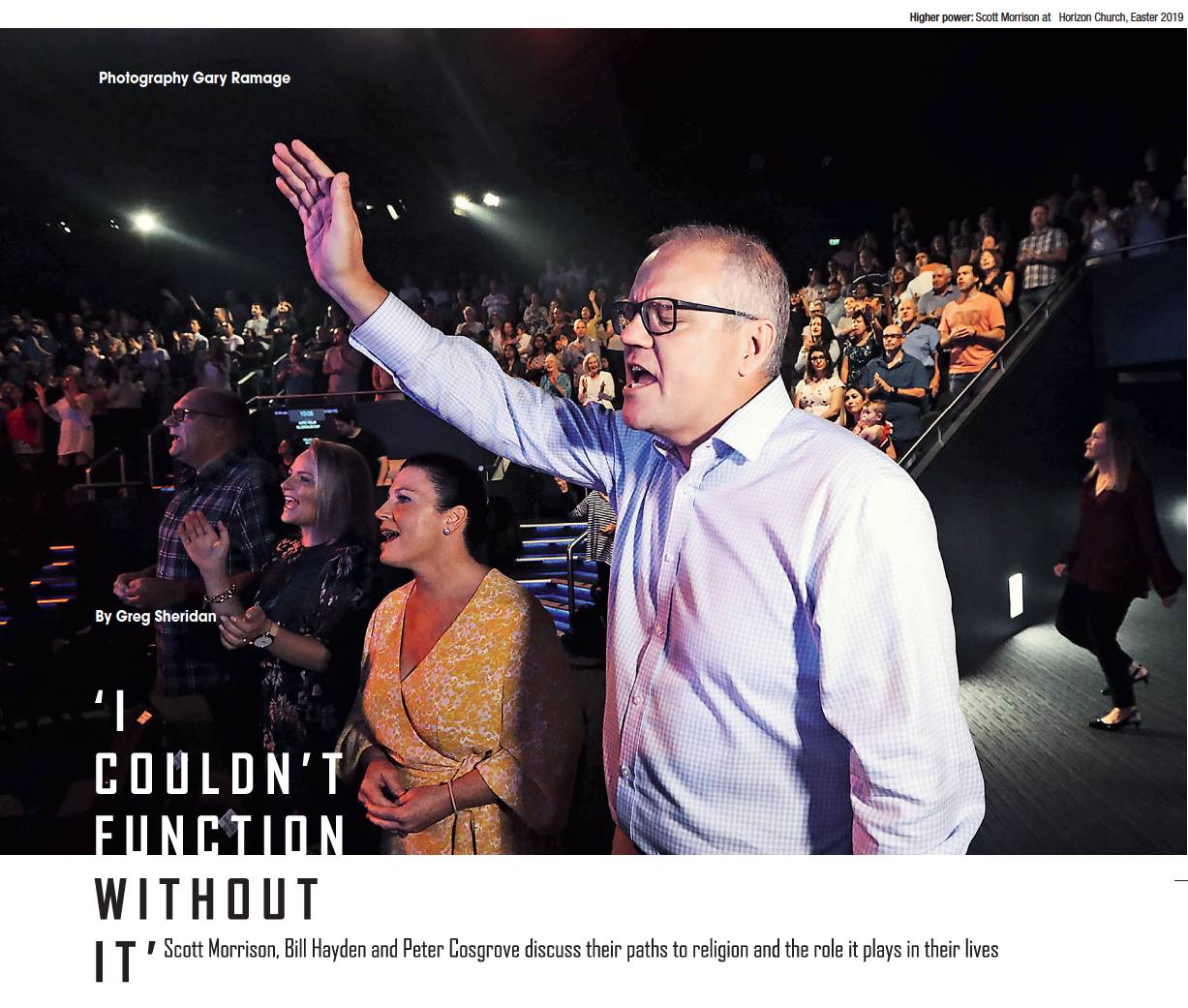

Higher Power: Scott Morrison at Horizon Church, Easter 2019

Scott Morrison gave his life to God, committing himself to the service of Jesus for the rest of his days, on January 11, 1981. He was 12 years old. He remembers the day and the moment with perfect clarity. He has never gone back on this promise.

When Morrison became Prime Minister in August 2018, he made religious history of a kind. He was the first member of a Pentecostal church to become Prime Minister of Australia and the first Pentecostal to become a national leader in any developed nation.

The nation has got to know Morrison as a man and a political leader. But they saw the Pentecostal dimension of his faith explicitly on one rare and striking occasion. At Easter, 2019, there he was on our TV sets and in the newspapers, in an open-neck shirt, right arm high in the sky, palm forward, eyes closed, swaying in song and prayer, at the Pentecostal Horizon Church that he and his family have attended since they moved to Sutherland Shire in Sydney’s south.

It was an arresting image, one we’d not seen before. Prime ministers at prayer are normally solemn, not to say po-faced, in the front pew of an Anglican or sometimes Catholic cathedral, at Christmas or Easter, well dressed in a suit and tie. We almost never see them in their own regular worship, and if we had done in the past, it wouldn’t have been like this.

Morrison doesn’t go out of his way to talk about his religious beliefs but he doesn’t hide them; he’s happy to share them if asked. When it’s relevant he’ll say a prayer, as for rain in a drought, but his religion doesn’t determine any policy matter. Both his parents were religious: “I grew up in the church. My mother is still going there. My father went there to the end [of his life]. Church life and community were wrapped up in one for us.” The church in question was the Presbyterian church at Waverley, in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, which later became part of the Uniting Church (which drew together Methodists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists).

Morrison’s choice to be an active Christian was emotional, intense and entirely personal. As a child, he attended with his family a huge Billy Graham crusade at Randwick Racecourse in 1979. Coincidentally, his future wife, Jenny, whom he had not yet met, was there too. By an even odder coincidence, so was I; an evangelical Anglican friend took me and another friend along. I found Graham impressive but I didn’t feel drawn to go down to the altar at the end and make a dramatic life commitment. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people did so that night, which is how Billy Graham crusades typically finished.

Morrison’s brother Alan did go down to the altar to make his own life’s commitment: “I have this lingering memory on the night, my brother went down and he was two years older than me. I talked it over with dad. Dad said, ‘Don’t go just because your brother did. Wait till the time is right for you.’”

When Morrison was in Year 7, he went to a Boys’ Brigade camp in Nunawading, Melbourne. “On that camp I gave my life to the Lord, on January 11, 1981. I was 12. I massively felt it that day,” Morrison says. “It is a confession of repentance. I felt that movement, to get to my feet. I spent the rest of the day sitting with the chaplain.”

In his late teens, his brother baptised him at the Christian Brethren Assembly at Waverley Gospel Chapel. “I met Jenny through their youth group,” Morrison says. “In Year 12 we started going out together.”

They married in 1990, just after Morrison finished university. It is well known that they struggled for 14 years, and many rounds of IVF treatment, to get pregnant. But they didn’t want it to dominate their whole lives, so they finally gave IVF away and then, miraculously, their two daughters were conceived naturally, with Jenny falling pregnant for the first time at 39. Morrison comments: “The biggest blessing is the girls. We never thought we’d have them. God is in the waiting. Faith gives you the confidence. Faith is the source of strength. You try to trust to the Lord. We had many prayers from Christian friends. Abby was born the seventh day of the seventh month, 2007.”

Morrison’s journey to the Pentecostals was gradual and fortuitous. In 2000 he got a job in New Zealand and he and Jenny went to church at the Christchurch Brethren Assembly: “They were a lot more charismatic [in style]. We had some wonderful pastors and friends there. I love that type of worship.”

The most controversial aspects of Pentecostalism are speaking in tongues and faith healing. Morrison says he doesn’t speak in tongues but these practices are much less strange than they might seem at first blush. Almost all Christians of all denominations pray for the sick and hope that their prayers will be answered. They, too, believe in faith healing. Speaking in tongues happens a lot in the New Testament. Pentecostals believe speaking in tongues is the Holy Spirit enabling them to pray. A friendly sceptic might view it as a kind of free-range vocalisation of the sentiment of prayer.

Morrison takes up the story: “When we came back to Australia in July 2000 we really appreciated that style of church and we started going to Hillsong church in Waterloo [in inner Sydney]. It’s a bit different from the one in the Hills. It suited us, it was big, we made a lot of friends. Later we went to ShireLive. It’s now called Horizon Church. I’ve never been that fussed about denominations. I just like a community, Bible-based church.”

Morrison tells me there are times when he has felt profoundly moved and comforted as fellow Christians have prayed over him. One highly unusual occasion Australians saw Morrison pray, and talk about praying, came in April 2021 when a video was taken of him speaking to the Australian Christian Conference, the national gathering of Pentecostals. He said: “I’ve been in evacuation centres where people thought I was just giving somebody a hug, and I was praying with them. God has been using us [Morrison and his wife Jenny] to provide some comfort and reassurance.” Morrison confirms to me that he only prays with people if they want him to, with their permission.

How does Morrison pray privately? “I try to pray every day. When I can I’ll get down on my knees. Getting down on your knees is a sign of complete dependence in your life. Other prayer is conversational, in the garden at home or wherever. Prayer is an important act of submission and acknowledgment. It involves humility, obedience, submission, faith and thanksgiving,” he says.

“The Bible is massively important to me. It’s got easier now that it’s on your mobile phone. This year I’ve been reading the Old Testament. I’m currently reading about Ruth. I read parts of the Gospel regularly. Faith is not passive. Faith is an active process of engaging with God. Generally I won’t talk about it too much. It’s got nothing to do with politics. It’s really relevant to me. I couldn’t function without it. My faith informed my life.”

Faith is central to Morrison and he brings his whole personality and values and principles to politics. But faith does not dictate his specific policies. Therefore he thinks it’s unfair, if someone disagrees with his policies, to attack his faith, or to claim he is trying to impose his faith on others through his policies.

Morrison took tough decisions about boat people when he was minister for immigration. He believes that what he did was morally justified and in the national interest. But at times he struggled emotionally with the grim situation. At home with Jenny he was in tears over the moral gravity of the decisions he felt he had to make. “Do I search my soul and spirit when I make a tough decision? Yes. The Bible is not a policy book. I do believe I did the right thing. It’s not that God told me to do it.”

Does Morrison believe in eternal life? “Absolutely.” Will he see his father again? “When we go to glory. I absolutely believe it.” Will we be judged on our lives? “Of course, we all are and we’ve all failed. That’s why Jesus came, to save, not judge. The doctrine of grace says that none of us gets there on our own. Of course I absolutely believe in eternal life.”

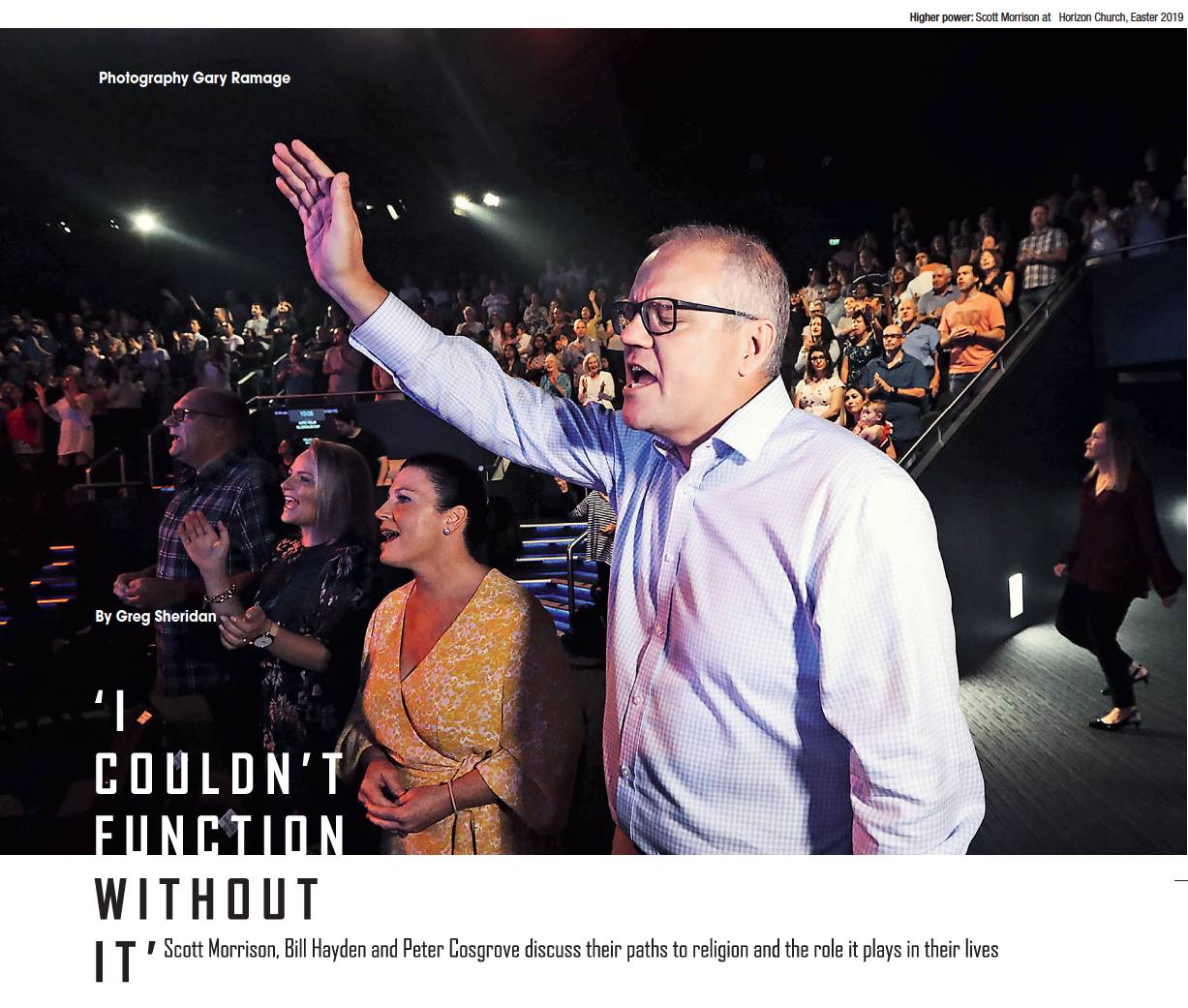

No one has ever doubted Bill Hayden’s basic decency. A sailor, a policeman, then a politician who did a university degree part-time while he was an MP, he came from an older Labor tradition. He could play his politics tough enough, and he held all the highest posts of government our nation has to offer except the prime ministership.

I was just starting out in journalism when Hayden (now 88) was opposition leader but I got to know him when he was governor- general and once or twice we talked a little about religious belief. Hayden was a conscientious and intellectually serious atheist. In 1996 he was named Australian Humanist of the Year. But when we talked, the conversation would often drift to God. I felt even then that Hayden was a decent and good man, caught in a continuing crisis of unbelief.

Nonetheless, he took his atheism seriously. At his swearing-in ceremony he made an affirmation rather than take an oath on the Bible. He felt his atheism prevented him from taking up the governor-general’s traditional role as head of the Boy Scout movement – the Boy Scout promise says, “I will do my best to do my duty to my God.” He wouldn’t make a promise to a God he didn’t believe in.

And then, in 2018, he announced he had abandoned his atheism and was embracing Catholicism, or, as we might put it, Catholic Christianity. His mother had been a Catholic. In primary school he was educated by the Ursuline nuns and he had gone to mass sometimes as a kid.

In late 2020 I sent him a note asking if I could talk to him about it. Because of Covid we had to speak over the phone, and he was in failing health. It was a draining effort for him to speak at all. There was only one question I really wanted to ask. Why did you come to the Christian faith, Bill?

“I couldn’t bear the emptiness,” he replied. “In my mind there was an emptiness without belief.” He also referred me to the influence of Sister Angela Mary Doyle: “She had been an administrator at the Mater Hospital in Brisbane for more than 20 years. She contacted me when I was in a terrible fight to bring in universal health care.” Hayden thinks her support was so important that there wouldn’t be Medicare today without the role she played in the politics of its introduction.

He tells me she also had a very direct influence on his religious homecoming: “A few years ago I went down to see her when she’d had a heart attack. The next day I had the sense that I’d been in the presence of a very holy person.” This had a profound effect on Hayden. In a letter he wrote to friends explaining his decision, he said of Sister Angela: “I’ve always felt embraced and loved by her Christian example… there’s been a gnawing pain in my heart and soul about what is the meaning of life, what’s my role in it. After dwelling on these things, I found my way back to the core of these beliefs in the Church.”

A critical factor in causing him to come to belief was meeting an old friend, a judge, in the Qantas lounge. “He said to me that the non- believer segment of our society is growing strongly. But our moral code is in the Bible and no one has put an alternative. It could be a disaster. That made me rethink my position... it played a role in my change. People like me and him who were atheists – I’d go to Humanist Society meetings and all they ever talk about is more money for education. They’re not talking about the deepest issues. Humanists should be talking about how we promote a society that’s decent. Humanism should be a life shared with others, and to create circumstances where others can be assisted.”

He goes to church when he can and he prays: “One of the great things is that most nights I say prayers for people who are in trouble. He might be surprised to hear it, but I say prayers for Graham Richardson because he’s in ill health and I pray for his speedy recovery.” Hayden repeats that line: “He might be surprised to hear that.” It sounds almost as though Hayden has surprised himself.

When Hayden came to Christian faith he said publicly that he wanted to vouch for God, he wanted to encourage people to come to God, he wanted to stand for belief, he wanted to help in St Vincent de Paul, he wanted to help poor people. In all this, with whatever strength he had, he was faithful.

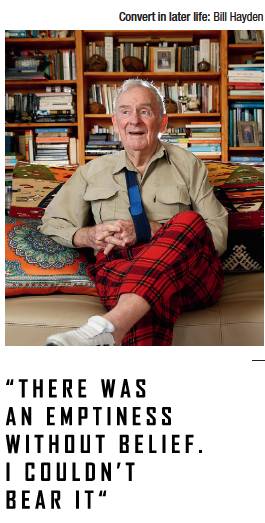

Peter Cosgrove was perhaps the most popular soldier in Australia in the past 50 years. Head of the international peacekeeping force in East Timor, Chief of Army, Chief of the Defence Force, Governor-General: it was a storied military career.

Cosgrove, 73, has always been a proud Catholic. Though you seldom hear him talk about religion, when you ask him about it, he’s very forthcoming. Cosgrove honours the tradition that spawned him: “My core was formed by a strong family. There’s a moral core which, if you deviate from, you are eating away at yourself.” What things comprise this moral core, what things must you be aware of? “Sin, the life hereafter, redemption, love, mercy and compassion.”

Cosgrove went first to a small Catholic primary school in Paddington, Sydney, then to the big Christian Brothers college at Waverley, near Bondi. He has mixed feelings about the Royal Military College at Duntroon: “A very rough and tough environment… secular and oppressive. There were church parades [going to services on Sundays] but you were out in the street, you were not in God’s house at Duntroon. That and bastardisation, I was a victim of it and later a perpetrator of it. It was not a Christian way to treat people. It was mostly the humiliation factor, reducing human dignity to an afterthought.” Bastardisation involved the endless humiliation of junior cadets, and their being given countless extra tasks, by senior cadets. Cosgrove as a senior was known as “a hard bastard”. He regrets and apologises for his ways then and has been fiercely opposed to such practices ever since.

Cosgrove has been a believing Christian all his life – even, especially, when he served in Vietnam. Did he pray in combat? “There were those informal moments of prayer, so frequent as not to be formal. There were those flashes of thought, those thanks to God that you and your men have survived… There was no thought of privileging a Christian over a non-Christian.”

How did it feel after combat to see enemy dead, people he or his soldiers had killed? “There was sadness at the sight of dead people. They are human beings, they have families too. Not remorse, because you’d done what your country asked you to, but sadness.”

What of the morality of soldiering? “The first Christians would not resist even to save their lives. But another side says that God has put us on Earth for the struggle [of life], to live until our natural end with dignity. Living with dignity means preserving freedoms. You need Christians to defend the rights of others whether they’re Christian or not. I came out of a military family grounded in World War I and World War II. These men were Catholics. I presumed the morality [of soldiering] had been worked out long ago.”

Cosgrove was the first Catholic Chief of the Defence Force (CDF), which seems a remarkable quirk in Australian history. But as CDF, and in other leadership roles before that, he was, he says, “very low key about the way I expressed my faith. I would stress morality rather than Christianity”.

Does he pray today? “I pray for the kids, the grandkids, for the government – I want them to get things right. I pray for the CDF. They say there are no atheists in foxholes. That’s too glib. A lot of atheists have performed very well in foxholes. But it is possibly true that everyone who is terribly scared clings to the hope that if the worst does happen, my spirit may live on…

“It’s important to believe, and to worry about the hereafter – which gate will you walk through?” he continues. “Life everlasting means a life well lived will be rewarded. I love the thought that I’ll meet again the people who have been important in my life. Not for a moment would I hesitate to say I am a man of faith.”

Edited extract from Christians, the Urgent Case for Jesus in our World by Greg Sheridan (Allen & Unwin, $32.95), out next week.

** End of Page

Go Top