BERNARD SALT

January 26th, 2017

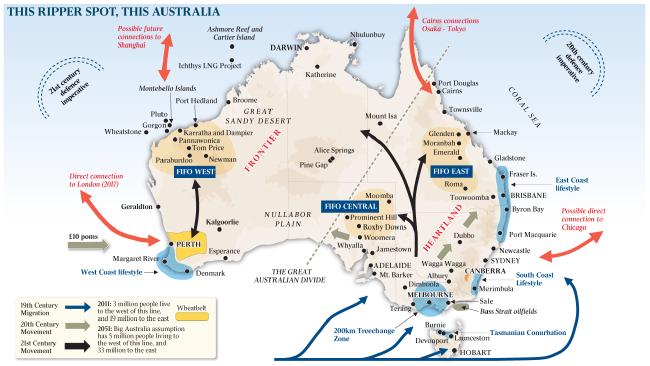

Welcome to Saltís Australia 2017. Toss out everything youíve ever known about the Australian continent and its people and let me show you how this place really works. Buckle up, because this could get bumpy.

Click here to see large image. Best viewed on desktop and tablet.

We are the Australian people and nation; thereís 24 million of us. More people live in Texas (27 million) than in Australia. We are the only nation on earth to claim sovereignty over an entire continent. Not even the Americans make such a claim Ö but we do. Not only that but we also have a suspended claim to one-third of the Antarctic continent.

We also claim sovereignty over a number of offshore islands ó some barely more than reefs ó including Christmas Island, Cocos and Keeling Islands, Ashmore Reef and Cartier Island, Coral Sea Islands, Heard Island, Norfolk Island, McDonald Island and Macquarie Island.

We snaffled the colony of New Guinea from Germany soon after WWI and promptly bolted it to Papua to make Papua New Guinea, before handing the lot back with independence in 1975.

There was a time in the 1840s when the Dominion of New Zealand was administered by the governor of NSW. And quite right too. Personally I think those Kiwis are yearning ó yearning, I tell you ó to be part of a greater United States of Australasia. Itís only a matter of time, my Kiwi friends, before you too will be speaking with an Aussie drawl.

We think all of these landholdings are ours, as indeed are the rights to surrounding waters for fishing and drilling purposes.

Not a bad land grab, I would have thought.

Which is why the Australian nation has always cozied up to the prevailing world superpower, namely the British in the 19th century and the Americans in the 20th century. Any ideas as to who will be the prevailing world super power in 2050? Look, it probably will be the US, so thereís nothing for the Australians to worry about.

When we worked out the Brits couldnít protect our interests after the fall of Singapore, the Australian prime minister John Curtin pleaded with the Americans (some say begged) to intervene and save us. Which they did at the Battle of the Coral Sea. And then after the war, the greatest military force the world has ever known politely left our shores.

How lucky are we? I mean why should boys from Kansas put their lives on the line to save the people of the Riverina? Whatís in it for them? After all, the Russians didnít entirely vacate lands they liberated after WWII.

The largest collection of military personnel assembled in one place on the Australian continent is located at Lavarack Barracks, Townsville. The reason is that this nationís 20th century threat came from the northeast, and itís probably a good idea to position military personnel between the population base and the likely direction of any perceived threat.

Then thereís Robertson Barracks in Darwin, which has included rotating US Marines since 2012 and Swanbourne-Campbell Barracks in Perth to protect the west. The top end is also protected by the RAAF at Katherine. If we are attacked from the north there are people who scramble in Katherine.

But thereís nothing to signal that Australians are actually putting their money and their military personnel where their mouth is on the North West Shelf. We have relatively new gasfields offshore at Gorgon and Wheatstone with no nearby military presence.

When Esso-BHP started drilling for oil in Bass Strait in the late 1960s the Victorian RAAF was relocated from Laverton to Sale. Even though modern fighter jets can get from Katherine to Karratha quickly, there is an argument that a mere military presence dissuades aggression.

Arguably the most important ports in Australia are Port Hedland for iron ore, Dampier for gas, Newcastle for coal, Fremantle for agribusiness and Melbourne for container traffic. The busiest airports are Sydney (27 million passenger movements) and Mel≠bourne (25 million), which also happen to be Australiaís most connected cities.

The overseas cities that Australians are most likely to connect with are Auckland and Denpasar. Sydney connects with 50 global cities; Melbourne connects with 30.

To put this into perspective, Londonís six international airports collectively connect directly with 350 cities outside Britain.

The vast majority (21 million) of the Australian nation lives east of a line that dissects the continent northeast and southwest. This line looks a bit like an unofficial idea floated during WWII when the Japanese were pressing towards Australia.

The idea involved conceding the bulk of the continent to the invaders and allowing the Australians to fall back behind a so-called Brisbane Line extending between Brisbane and Adelaide. The French did this in 1940 conceding Paris, the north of France and the Atlantic coast to Nazi control. Seventy-five years later and the Brisbane Line might be tilted a bit further north to Cairns and a bit further west beyond Whyalla.

Australiaís wealth comes from mineral and energy exports mined and tapped in the Pilbara, at Roxby Downs and in the Bowen Basin. Australians donít want to live in these places; we would rather fly-in fly-out (FIFO) forever into the future. The idea of place-making or town-building died out in the late 20th century in favour of the FIFO solution, which is apparently now cheaper than building a town.

And besides, modern Australians would rather live in sea≠change or tree-change com≠munities than in remote locations. The last permanent town to have been built in the Australian Outback is Roxby Downs, which was opened in the late 1980s near the Olympic Dam copper and uranium mine in South Australia.

The Australian heartland of sheep and cattle grazing lands covers the Murray-Darling Basin that extends west of the Great Dividing Range and which includes cities like Toowoomba, Canberra, Albury, Dubbo and Wagga.

The coastal "sea-change" strip extending between Merimbula and Port Douglas contains 11 million people including Sydney with five million and Southeast Queensland with more than three million residents. An inland lifestyle zone extending 200km from the big capital cities forms what Australians refer as the tree≠change belt.

The Great Australian Outback, even generously defined, contains less than 200,000 people despite covering one-third of the continent. Itís akin to Russiaís Siberia or to the African Sahara in terms of sparseness of population.

We allowed the British to detonate atomic weapons on the Montebello Islands off Western Australia in the 1950s and on the mainland at the Woomera testing range in the 1960s. We allow the Americans to operate a southern hemisphere data gathering facility at Pine Gap near Alice Springs.

Sydney and Melbourne dominate business on the Australian continent by containing seven of the nationís eight Fortune 500 businesses. Only Perthís Wesfarmers (Coles & Bunnings) bucks the east coast trend.

By the middle of this century Sydney and Melbourne will approach eight million residents. Southeast Queensland is expected to contain five million. Australia as a whole is likely to contain 38 million by 2051 based on Big Australia migration assumptions.

However, new official projections based on the 2016 census results (and to be released later this year) could show the first moderated projection of Australiaís mid-century population in 20 years.

The issues and challenges facing the Australian nation in coming decades will pivot around military alliances and access to trading markets. We produce far more than we consume. Trading is the basis to our standard of living. A trade war would have a devastating impact on the lifestyle we have become accustomed to. We need open and friendly markets. We need friendly superpower support. What happens in America, China or Europe matters here.

We are the down-under island-nation of Australia, more secure and richer than most.

We should be a prosperous people for 100 years purely on the basis of the scale of our resources relative to the scale of our population base.

There is every reason to have every confidence in this land, this ripper spot, this Australia.

Bernard Salt is a KPMG partner and an adjunct professor at Curtin University Business School. Map by Cody Phelan and Kellie Southan.

bsalt@kpmg.com.au